What is the latest on the "High Seas Treaty"?

Fifth Session of the Intergovernmental Conference on Marine Biodiversity Beyond National Jurisdiction

We may not think about it often, but our lives draw and depend on the ocean.

More than 80% of all goods we consume are transported via the ocean, the ocean absorbs around 30% of the carbon dioxide that we release into the atmosphere and 17% of our food comes from the ocean. Our internet connection relies on submarine cables and we use cosmetics that include marine extracts, not to say about the importance of marine bacteria to produce tests to detect Covid-19.

How do we make sure these activities can continue to happen without pushing the ocean to a tipping point where it collapses and can no longer provide us with all these ‘services’ anymore?

-full.webp)

Regulating the uses of the ocean has been one of the responses to this question. The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), adopted in 1982, is the “constitution for the oceans” attracting near-universal acceptance. Forty years after, the international community is negotiating an implementing agreement under the UNCLOS framework on the conservation and sustainable use of marine biodiversity in areas beyond national jurisdiction (BBNJ), often referred to as the ‘High Seas Treaty’ (NB: while the term is imprecise as it is not yet clear what areas beyond national jurisdiction the agreement will cover, we will employ it here at times to avoid acronyms).

Considering the increasing pressure on the marine environment by habitat destruction, overfishing, marine pollution, ocean acidification, etc., the BBNJ agreement is a significant step to fill normative gaps under UNCLOS. The negotiation is also meaningful to close implementation gaps concerning UNCLOS’ provisions to reduce worldwide scientific and technological asymmetries, which is fundamental to promoting the human right to science.

Despite its critical importance for humankind, the BBNJ negotiations have not become a catchy topic in the public discourse. There are several reasons for this: Areas beyond national jurisdiction (ABNJ), which are the High Seas and the corresponding ocean floor, are literally invisible to most people. In addition, the negotiations are complex to follow because they demand some understanding of science, law and policy, and heavily use acronyms, not attractive to most people.

This blog post hopes to break the bubble by sharing my perspective on the core topics discussed in the fifth session of the intergovernmental conference on BBNJ (IGC5-BBNJ), underlining reassuring points of advance and the many pending issues. Because as “nothing is agreed until everything is agreed”, the question looms whether marine biodiversity will make it until states agree.

What is the 'High Seas Treaty'?

Discussions to create a new agreement on the oceans started 18 years ago, in 2004, when the UN General Assembly established an Ad Hoc Open-ended Informal Working Group to study the socio-economic aspects of the conservation and sustainable use of marine BBNJ and propose legal options.

In 2011, the working group recommended a “package” of themes to be addressed by a future legal instrument which remained the ones currently at stake and discussed in this article. Further steps were taken in 2015, with the decision to establish a preparatory committee, and in 2017, when the decision to convene an intergovernmental conference to discuss the agreement was taken.

IGC1 was held from 4-18 September 2018, IGC2 took place between 25 March and 5 April 2019, IGC3 was convened from 19-30 August 2019. The Covid-19 outbreak highly affected the negotiations leading to multiple postponements of the fourth session and inaugurating what has been called “digital multilateralism”. IGC4 was finally held from 7-18 March 2022 with limitations on the number of delegates in the room and restricting civil society participation, resulting in few content advances. A fifth session (IGC5) was convened from 15-26 August 2022. For more detail, see a treaty timeline by the High Seas Alliance.

Which issues are discussed under the 'High Seas Treaty'?

As an implementation agreement, the new instrument will be much more focused than UNCLOS, addressing four topics:

- Area-based management tools (ABMTs), including marine protected areas (MPAs): The idea is to protect the ecosystem and biodiversity in a certain area by limiting some or all human activities, e.g. fishing, navigation or other exploitation, laying of cables, scientific research;

- Environmental impact assessments (EIAs): This is about countries requiring companies to evaluate the effects of a proposed activity on the marine environment with the potential to restrain certain activities which may cause major impact;

- Capacity building and the transfer of marine technology (CB&TMT): These measures try to ensure that countries are equally able to implement the agreement and contribute to the sustainable use and conservation of the ocean; and

- Marine genetic resources (MGRs), including questions on benefit-sharing: This is about accessing, collecting and subsequently utilising materials from marine organisms and how to share fairly the benefits resulting from extracting these resources, e.g. by ensuring cooperation and transfer of knowledge and technology (non-monetary benefits) or companies paying money to relevant countries or into a fund (monetary benefits).

Two of the package themes, ABMT and EIA, target primarily the conservation of marine BBNJ, which is not yet comprehensively regulated at a global level. MGRs and CB&TMT also aim to promote the conservation and sustainable use of resources but bring to the forefront the need for equity.

Very importantly: None of the issues are stand-alone themes and states decided that they must be addressed “together and as a whole”. In addition, the new instrument will address cross-cutting issues like the agreement’s relation with other international instruments and institutions, regional and sectoral treaties and bodies, principles, new institutional arrangements, funding, and dispute settlement.

I have been following the negotiation from a distance since the start, in particular MGRs, CB&TMT, the agreement’s relation with UNCLOS and dispute settlement. Recently, I had the opportunity to attend the second week of IGC5 in person as part of the Deep-Ocean Stewardship Initiative (DOSI) delegation and in collaboration with WoMen+Sea.

What are the latest developments on the 'High Seas Treaty'?

Even participating remotely in the first week of IGC5, I could notice an invigorated engagement of all delegations as part of a joint effort to finalise the agreement at that session. Many of them stressed the need for a future-proof agreement, and advances were achieved on less controversial elements of the text. It was clear that everyone agreed that the treaty was a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to protect marine biodiversity in ABNJ.

In the middle of the second week, the mood changed drastically. Divergences on “how” to protect biodiversity, the extent to which States were willing to curtail the freedom of the seas, the relation between the agreement and other instruments already in place and the mandate of the Conference of the Parties (COP) took the foreground. In an attempt to speed up the agreement’s adoption, the President and facilitators favoured small group discussions and closed meetings. On the one hand, such a strategy enabled considerable movement on certain topics and favoured identifying thorny issues. On the other hand, some countries expressed concern, especially the ones with smaller delegations, about the lack of transparency and opportunities for coordination within regions and with capitals.

In the end, outstanding points of disagreement prevented States from adopting an instrument, although many delegations emphasised that advances were achieved at IGC5, particularly in comparison with the previous session. Overall, it caught my attention that the division between so-called developed and developing States, which also underpinned UNCLOS’s negotiations, was again guiding the positions.

The Small Island Developing States (SIDS) emerged as relevant actors advocating for recognizing their special circumstances through the agreement (which is being recognized as a new development compared to their standing at the UNCLOS’s negotiations). The Pacific SIDS were particularly ambitious on many of the conservation items. Also, the new draft agreement brings provisions on free, prior and informed consent from indigenous peoples prior to accessing traditional knowledge, and on promoting gender balance in all institutional arrangements.

Where do states (dis)agree on the 'High Seas Treaty'? Advances and Pending Issues

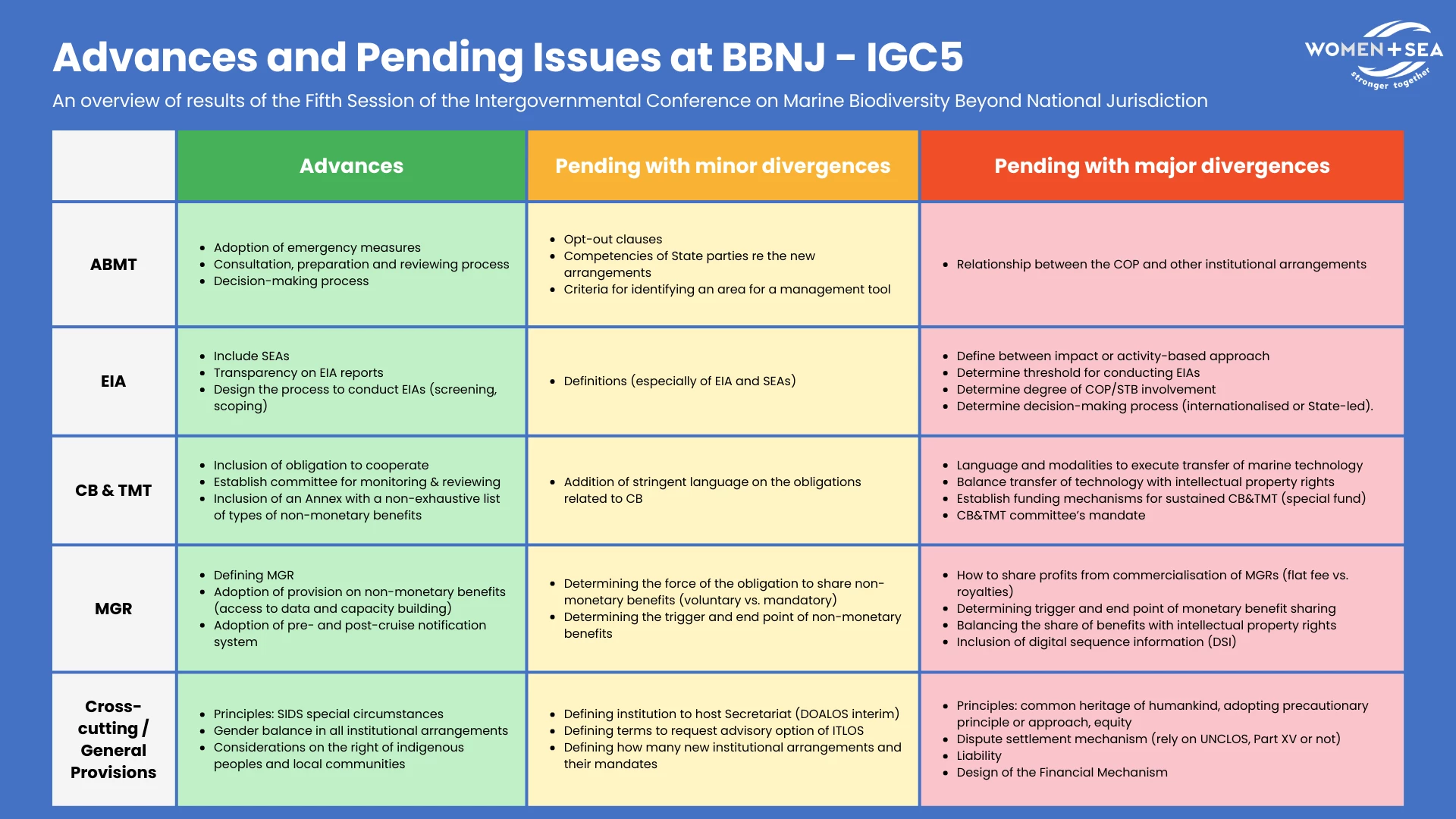

Based on my notes, corridor discussions, and grey literature (blogposts, news, reviews), including the Earth Negotiation Bulletin reports, the following advances and pending issues (minor and major) can be summarized:

Overview of advances and pending issues at the latest session on the 'High Seas Treaty'

More specifically, this means:

-

Area Based Management Tools (ABMT): Compromise was reached on including emergency measures in case an activity presents serious threats to the marine environment; the consultation, preparation and review process; and decision-making. Agreement is still pending on the “opt-out” clauses, which allow States to pull out of a certain ABMT regulation; the competencies of State-parties vis-à-vis the new institutional arrangements; and the relationship between the COP and other institutional arrangements in place, such as International Fisheries Bodies (IFBs) and Regional Seas Programmes (RSPs).

-

Environmental Impact Assessments (EIAs): States managed to streamline the text and agreed to include (broader) strategic environmental assessments (SEAs) and on the process to conduct EIAs. Major differences remain concerning definitions, adopting an impact or activity-based approach, the threshold for conducting EIAs, and the decision-making process (internationalised or State-led).

-

Capacity Building and The Transfer of Marine Technology (CB&TMT): States agreed to include an Annex with a non-exhaustive list of non-monetary benefit types and to establish a committee for monitoring and reviewing the treaty’s implementation. However, the committee’s mandate is still disputed, with developed States advocating for including resource mobilization whereas developing States aim for a standing committee on finance. Discussions on the language of the obligations (“undertake to provide” vs. “shall provide”) were moved from the informal informals to small group discussions with no apparent decision. Agreement is still pending on how to execute the obligation to transfer marine technology, to reconcile the transfer of technology with intellectual property rights and funding mechanisms for sustained CB&TMT. Contrary to many of IGC5’s reviews consulted for this post, I see such unsolved issues as major because they have already led to key implementation gaps of UNCLOS and therefore carry the risk of undermining the new agreement as well.

-

Marine Genetic Resources (MGRs) seemed to be the most polarised theme of IGC5, where finding common ground would likely be decisive for the subsequent adoption of the instrument. One major sticking point since the beginning of the BBNJ negotiations is whether or not monetary benefit-sharing should be included. Over the course of the session, the idea of decoupling the provisions from access from those of benefit-sharing (ABS) paved the way to advance compromises on several elements, including non-monetary benefits such as pre- and post-cruise notifications (e.g., to enable participation by developing country scientists). My view is that the non-monetary benefits were less controversial because they mostly replicate worldwide accepted provisions enshrined in Part XIII of UNCLOS – which include information to be provided before accessing MGRs, access to data and capacity building. Despite that, it is still unclear whether this would be a voluntary or mandatory obligation and what would be its triggering and endpoints. Flexibility on the track and trace system – which allows tracing the origin of a MGR and identifying when benefit sharing is needed - provided room to attract support from developed countries for monetary benefits. In the last few days, delegations proposed several new ideas and potential avenues for compromise were identified. Still, there was little time to think them through or coordinate within regions or with capitals. The remaining divergences include if and how to share profits from the commercialisation of MGRs, the triggering point for the obligation to share monetary benefits, how to reconcile the sharing of benefits with intellectual property rights and whether digital sequence information (DSI), i.e. the effective and equitable sharing of DNA and RNA data on organisms, will be covered by the treaty.

- General provisions and cross-cutting issues: There is a huge gap in the text regarding liability for damages to the marine environment in ABNJ; points of division include the adoption of the precautionary principle or approach; the inclusion of MGRs in the principle of the common heritage of humankind; which body will host the agreement’s Secretariat - with strong support for the United National Division for Oceans Affairs and the Law of the Sea (DOALOS) as interim Secretariat; budgetary obligations; and dispute settlement mechanism – including whether the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea will have the mandate to provide advisory opinions on BBNJ-related topics. One of the most significant points of divide – which, surprisingly, is not much explored in the literature consulted - is the Financial Mechanism, which is likely to impact the implementation of the entire instrument.

Participants during a well-attended evening plenary at BBNJ IGC-5 (Photo by IISD/ENB | Diego Noguera)

What happens next on the 'High Seas Treaty'?

President Rena Lee suspended the negotiations, which will likely be resumed in early 2023. I left New York City with a mixture of hope and concern, and I dare to say, similar feelings were shared among other participants.

Hope comes from seeing that delegations seemed to be genuinely working towards a timely conclusion. As a result, compromises were reached on more aspects than in previous sessions. Concern comes from understanding that establishing a monetary access and benefit sharing (ABS) system, operationalizing EIAs in ABNJ and creating a mechanism to promote sustainable funding for CB&TMT are not minor issues to be solved, involving long-standing divides, and economic and geopolitical considerations. Lastly, strategies adopted in the final days, e.g. re-discussing aspects that seemed to have already been settled in previous sessions, reveal that caution is needed; after all, nothing is agreed until everything is agreed.

It is indisputable that marine biodiversity will not wait forever for an agreement. As mentioned, at the outset, the success or failure of the next ICG will affect us all, whether we are working on, living by or merely benefitting from the ocean through food, commerce, energy, lifestyle products or connectivity. Echoing the words of Greta Thunberg “politicians do not need to wait for anyone else in order to start taking action. Nor do they need conferences, treaties, international agreements or outside pressure. They could start right away.” During the intersectional period, politicians must continue to exchange views and proposals informally to pave the way for a treaty adoption in the next conference.

Might there be a way for other actors concerned with the outcomes of the negotiation, such as academics and private entities, to get involved and facilitate? Watch this space, we will share some ideas soon!

Bottom Line

-

An additional treaty to promote the conservation and sustainable use of marine biodiversity in areas beyond national jurisdiction (BBNJ) for present and future generations is under discussion, which also aims to promote scientific and technological equity among States.

-

The core elements under negotiation are marine genetic resources (MGRs), area-based management tools (ABMTs), environmental impact assessments (EIAs) and capacity building and the transfer of marine technology (CB&TMT).

-

States were unable to agree on the treaty at this stage – the thorniest issues were monetary benefit-sharing, the operationalisation of EIA, and the terms to fund and transfer marine technology.

-

It is fundamental to establish an ambitious and strong financial mechanism to enable implementation of the treaty.

-

The negotiations were suspended and will likely resume in early 2023.

Acknowledgements: I would like to extend sincere gratitude for the valuable contribution to the post provided by many contributors including Mr Philippe Raposo, Ms Klaudija Cremers, Mr. Daniel Kachelriess and Professor Carina Oliveira.

References

- Coelho, L. F. Does everyone have the right to share in marine scientific advancement and its benefits?

- Coelho, L. F. (2022). Marine Scientific Research and Small Island Developing States in the Twenty-First Century: Appraising the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, The International Journal of Marine and Coastal Law, 37(3), 493-528.

- High Seas Alliance, Treaty Talks End Without Resolution in New York

- Heffernan, O. Who Owns the Ocean’s Genes? Tension on the High Seas

- IISD, 5th Session of the Intergovernmental Conference (IGC) on the BBNJ

- IDDRI, Bringing the ship to shore: Significant progress towards a high seas biodiversity treaty

- Koh, T.T.B. A Constitution for the Oceans

- Maripoldata, Too High Hopes for a High Seas Treaty?

- Maripoldata, Finalizing an Ocean Treaty: Drowning in detail or sailing towards compromise?

- Maripoldata and One Ocean Hub, Participation at BBNJ Negotiations Matters

- One Ocean Hub, Contributing to the UN Negotiations of a New ‘High Seas Treaty’

- Ruiz, S. and Vadrot, A. The emergence of digital multilateralism

Back to insights

Back to insights